2022 Midyear Report on Vietnam’s Political Prisoners

This report is a brief update on arrests, trials, and prison conditions of Vietnamese activists during the first six months of 2022. The data was extracted from The 88 Project Database, which is constantly updated as new information becomes available. The report is divided into three sections: Arrests, Trials, and Prison Conditions.

1a. New Arrests

Truong Van Dung

In the first six months of 2022, there were a total of 15 new arrests as the crackdown on freedom of expression continued unabated. Of those arrested, seven are defendants in the same case involving a Buddhist temple. In the other eight cases, authorities arrested both well-known activists and people who had only posted about their opinions on social media. The wide array of arrests demonstrates the government’s unceasing clampdown on multiple forms of dissent.

As was the case in 2021, many people (nine) were charged under Article 331, which is often described as “abuse of democratic freedoms.” Conversely, the number of charges involving Article 117 — or “anti-State propaganda” – was only three. Interestingly, there also was one person, Truong Van Dung, arrested for “anti-State propaganda” but charged under Article 88 of the older 1999 Criminal Code.

Bloggers, YouTubers, and online commentators– individuals who simply post or comment on social media– continue to be targeted by the state. Religious leaders who use social media to communicate with their followers were also persecuted for expressing their opinions or beliefs online.

1b. Breakdown of Arrests

Husband and wife Nguyen Thai Hung and Vu Thi Kim Hoang

Perhaps most disturbing, and cause for international concern, is the criminalization of nonprofit sector leaders, such as the charge of “tax evasion” against prominent environmentalist Nguy Thi Khanh. This appears to represent another unwelcome trend, as Khanh was the fourth arrestee within the past twelve months who came from the traditionally depoliticized world of NGOs.

Nguy Thi Khanh is but one of four women arrested so far this year. In January, Vu Thi Kim Hoang was arrested along with her husband and charged with “abusing democratic freedoms” simply for reposting posts of other people about events such as the Dong Tam police raid. Hoang’s husband, Nguyen Thai Hung, ran a modestly popular Youtube channel that had about 40,000 subscribers before it was shut down due to his arrest. It’s not clear who is taking care of the couple’s two young children.

The two other women, Nguyen Phuong Hang and Cao Thi Cuc, were part of a highly unusual case involving a Buddhist Zen temple named Tinh That Bong Lai in Long An Province. The temple, which also serves as an orphanage, is run by a 90-year-old monk named Le Tung Van. Some of his disciples have a YouTube channel where they post their musical performances; the group has won several singing competitions. Their celebrity status led to an avalanche of online attacks and accusations including everything from financial fraud to sexual molestation. Leading the false charges was the above-named Nguyen Phuong Hang, a successful businesswoman and influencer whose husband is an oligarch in Vietnam. Also involved in these online attacks, as well as physical altercations, were several Buddhist leaders and the Long An provincial police, some of whom are both plaintiff and investigator in the case.

In January, authorities arrested Van and three of his disciples, charging them with multiple crimes. Finally in May the police also arrested Cao Thi Cuc, the landlord who leased the property to Tinh That Bong Lai, as well as another monk. In June, however, the authorities suddenly withdrew all the charges against the group except for one, “abuse of democratic freedoms.” Lawyers for the group have filed a lengthy complaint listing irregularities in the way the case was investigated; they demanded that the case be dismissed for violating prosecutorial procedures. However, the case is still slated to be tried in late July.

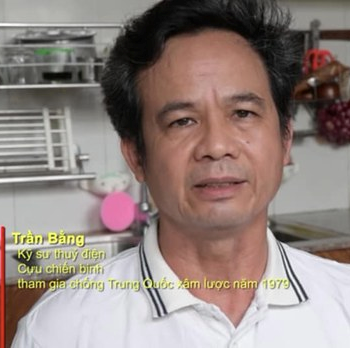

Three people so far in 2022 were charged under Article 117: Viet-Sino War veteran Tran Van Bang, a long-time advocate for multi-party democracy and member of an anti-China online group; Le Manh Ha, a self-taught law expert on land rights who has a YouTube channel dedicated to helping land grab victims; and Nguyen Duc Hung, a Facebooker whose postings and opinions were deemed to be “anti-state propaganda.”

Popular Facebooker Dang Nhu Quynh, whose account once had over 300,000 followers, was arrested in April and charged under Article 331 for postings centered on women’s rights, public health, corruption, and economic reforms.

2a. Trials

As of the time of this writing, a total of 18 political prisoners had been put on trial in 2022. Seven people were convicted of “abuse of democratic freedoms” (Article 331) and five of spreading “anti-State propaganda” (Article 117). Six were given prison sentences ranging from five to nine years, while six others received sentences of four years or less. Five individuals were media workers who had worked for the state at some point. Three are prominent civil society leaders. Most of these individuals were arrested last year and have spent all their time in pre-trial detention incommunicado without access to their lawyers or families.

2b. Breakdown of Trials

Dang Dinh Bach

Nguy Thi Khanh, the 2018 Goldman Environmental Prize winner, was sentenced in June to two years in prison for “tax evasion.” In an unusual decision by the court, Khanh’s husband was allowed to attend her trial. Khanh’s arrest has garnered tremendous international attention due to her name recognition and her staunch anti-coal advocacy, which could be the underlying reason for her conviction.

Two other prominent leaders of Vietnamese NGOs were earlier convicted of “tax evasion” as well. Mai Phan Loi, founder and director of the nonprofit Center for Media in Educating Community (MEC), was sentenced to four years in prison on “tax fraud” charges on January 11. Dang Dinh Bach, director of the non-profit Law and Policy of Sustainable Development (LPSD), was sentenced on January 24 also on tax charges. Neither man’s family was allowed inside the courtroom. An associate of Loi named Bach Hung Duong also received a somewhat lighter sentence of two years and six months for allegedly helping Loi evade taxes. Many analysts believe that the ongoing crackdown against these NGOs is related to their attempts to build a coalition of NGOs to oversee government compliance with rights provisions in a trade deal between the EU and Vietnam.

Five people have been convicted under Article 117 in 2022. Everyone tried under this charge was sentenced to five or more years in prison for conducting “anti-state propaganda.” Three of them operated popular Facebook accounts and two have no known history of activism but were nonetheless given harsh prison sentences. Tran Hoang Huan received eight years in prison plus three years of home surveillance; Nguyen Duy Linh received five years; and Nguyen Bao Tien, who delivered only a handful of books for the independent Liberal Publishing House, was sentenced to six years.

Two well known activists were sentenced to five years each for posting video clips that allegedly “defame the Communist party”: Dinh Van Hai, a Facebooker who was beaten by police thugs while visiting another activist in 2018, and Le Van Dung (aka Le Dung Vova), a well-known blogger and longtime pro-democracy activist from Hanoi.

Phan Bui Bao Thy (L) and co-defendants on trial March 30, 2022, Source: Toui Tre

Of the seven individuals convicted under Article 331, three were former journalists working for the state: Le Thi Thu Huong was sentenced to one year and nine months for her Facebook posts; Nguyen Hoai Nam, a decorated journalist who has won multiple awards, was sentenced to three and a half years for, again, his online posts; Phan Bui Bao Thy, who worked for the newspaper Education of the Times (Giáo Dục và Thời Đại), was given one year of “non-custodial re-education” along with another individual, Le Anh Dung, for “defaming the government” by exposing police corruption. A third person also arrested in this defamation case, former police officer Nguyen Huy, was convicted but not sentenced to prison time.

In another police corruption case, former police captain Le Chi Thanh was given an additional three years in prison in a second trial in June, on top of the two year sentence he had been given in January. Thanh was accused of making Facebook posts that allegedly were “false and that damaged the reputation of individuals in the police force, the prison system and the courts.”

Y Wo Nie, an ethnic Ede activist, was also sentenced to four years in prison for “anti-state propaganda.” The court claimed that Nie had been invited to meet representatives from the U.S. Embassy in Vietnam and participated in several online workshops on religious beliefs and protection, Vietnam’s civil law, and international human rights law.

In a bizarre twist, Le Trong Hung and Trinh Ba Phuong reported that they were taken against their will to appeal trials that they never requested. No lawyers were present and the trials didn’t result in any changes to their sentences.

- Prison Conditions

Nguyen Thuy Hanh

Overall, the conditions of life behind bars for political prisoners remain poor, with healthcare being the most pressing issue.

In one particular instance, Pham Chi Dung refused to eat his meat and fish ration in order to protest against his fellow political prisoners being denied dental treatment and medicine. Another prisoner, Huynh Duc Thanh Binh, said many political prisoners in his cell suffered from toothaches, making it hard for them to chew. He also said prisoners don’t receive adequate medical treatment despite their deteriorating health.

To make matters worse, prison authorities can, and often do, arbitrarily make it difficult for families to visit or send supplies such as food and medicine. The problem is exacerbated in cases where the prisoner is transferred far from their hometown; at least five such cases have been reported so far this year.

On the mental health front, at least three political prisoners — Nguyen Thuy Hanh, Nguyen Trung Linh and Le Anh Hung – were at some point transferred to a mental health ward. This was done either because they were suffering from mental stress, like Hanh, or as a way of pressuring them to cooperate with investigators (Le Anh Hung). It has also been reported in the past that this practice has sometimes been used as a way to humiliate and/or break prisoners deemed too intransigent.

Regarding COVID-19, it’s not known if and to what extent political prisoners are vaccinated. At least three positive cases have been reported thus far but, fortunately, all three have fully recovered.

On the “good news” front, Ho Duc Hoa was released early from prison and sent into exile in the United States, as was former political prisoner Tran Thi Thuy, ahead of Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh’s first visit to Washington in May.

Continued Risks

Pham Doan Trang

Bui Thi Thien Can, mother of award-winning activist and writer Pham Doan Trang who is serving a nine year sentence for “anti-state propaganda,” was allowed to travel to Geneva in early June to accept the Martin Ennals Human Rights Award on her daughter’s behalf. While in Switzerland, she was also able to meet with representatives from multiple governments and international human rights organizations to advocate for the release of her daughter and other political prisoners. Upon returning to Vietnam, however, Bui was questioned for four hours by police at Noi Bai Airport before being allowed to go home.

It should be noted that the risk of harassment against activists, as well as regular citizens such as Bui, remains high and can take on many forms. Poet Thai Hao, for example, was physically attacked by “strangers” when he traveled to Ho Chi Minh City in March to receive an award from Van Viet — an independent literary association considered “reactionary” by the government. The assault caused another award recipient, Nguyen Thi Tinh Thy, to later decline accepting her award out of fear.

Many people, activist and non-activist alike, privately express concerns that their social media activities are constantly monitored by online spies. Consequently, most practice self censorship either to avoid trouble or, as is more often the case, being heckled and verbally abused by state backed troll groups.

Lastly, it must be noted that journalists in general, state-sanctioned or otherwise, remain under constant pressure to toe the party line and steer clear of sensitive subjects. Four journalists and one blogger have been convicted already in 2022, and another three bloggers have been arrested. It comes as no surprise that Vietnam is currently ranked 174 out of 180 on Reporters Sans Frontière’s latest World Press Freedom Index, with consistently low scores in the Safety and Legal contexts.

© 2022 The 88 Project