Freedom of the Press under Renewed Siege in Vietnam

Six months into 2020, the intensive crackdown against activists and journalists carried out by the Vietnamese government continues. Its latest victim includes arguably the last independent journalist organization in the country.

On May 23, 2020, Nguyen Tuong Thuy was arrested and his apartment searched by the Public Security Department of Hanoi. Thuy, a 70-year-old military veteran, is currently the vice president of the Independent Journalists Association of Vietnam (IJAVN). Then, on June 12, 2020, the Public Security Department of Ho Chi Minh City arrested Le Huu Minh Tuan, another member of IJAVN. Pham Chi Dung, IJAVN’s president, was arrested in November last year.

IJAVN’s President Pham Chi Dung in a 2016 demonstration against China’s aggressions in the China Sea. Source

The new attack on an association of journalists might seem expected in the current political climate of Vietnam. Yet, it also reflects a much deeper and more systematic issue concerning the institutional suppression of journalism in the country. This article examines how and why the Vietnamese government still completely controls the Vietnamese media and also offers a historical explanation for the contemporary situation of the profession.

The legal framework of state-sanctioned journalism

According to Luat Khoa tap chi, private companies are behind many “general information websites,” which are only allowed to repost news and articles from other official registered news agencies, in accordance with Article 36 of the Law on the Press of 2016. However, with their own staff and resources, these organizations produce their own news and stories, then pay to publish them in recognized newspapers to finalize the legitimization process, before reposting the same articles on their own websites. With this reality, some observers suggest that freedom of the press has a de facto status in Vietnam. Some observers even argue that Vietnam has an independent force of journalists that can operate freely in the country. This proposition, however, misses the point of freedom of the press.

To begin with, the very existence in Vietnam of a legal definition of who can be a “journalist” in itself can be a threat to freedom of the press, and it affects what a proper framework for journalist protection should look like.

International law has yet to define a “journalist,” and maybe for good reason.

According to Professor Nicholas Tsagourias, University of Sheffield, in the United Kingdom, there might be no legal instrument specifically related to journalists, but most human rights instruments – international or regional – contain provisions protecting the right to life, the right not to be tortured or subjected to degrading or inhuman treatment, the right to liberty and security, or the right to freedom of expression. Because freedom of expression is a basic human right, any person engaged in the public expression of information or ideas should be protected by any possible means, with or without the official status of a journalist.

Other credible international organizations recognize this approach. In a 2012 report by Frank La Rue, the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression, journalism is considered an activity that can be practiced by virtually everyone. The report insists that “Such a definition of journalists includes all media workers and support staff, as well as community media workers and so-called ‘citizen journalists’ when they momentarily play that role.”

More importantly, the Human Rights Committee, in its General Comment No. 34, has also adopted a functional definition of journalism instead of specifying the criteria for being a journalist. They define journalism as “a function shared by a wide range of actors, including professional full-time reporters and analysts, as well as bloggers and others who engage in forms of self-publication in print, on the Internet or elsewhere.”

The idea of good journalism within the framework of the international law of human rights is that everyone can be protected in gathering and disseminating news. Trying to legally restrict the concept of “journalist” paves the way for governments to also encircle these essential rights as a privilege limited to authorized groups, with incentives, powers, and protection that only the government can offer. This, however, is precisely the government approach to journalism in Vietnam.

According to the 1989 Law on the Press, the old legislation defined journalists as:

“…Vietnamese citizens;

those who have a permanent residence in Vietnam;

those who meet all political, moral, and professional requirements as stipulated by the State;

Those currently employed by a lawful press agency in Vietnam;

Those who have been issued a journalist card by the Ministry of Information and Communications (MIC).”

The new Law on the Press enacted in 2016 maintains these elements in Article 27.

This legal framework allows the government to become the only judge in deciding who can and who cannot participate in the news-making process and ultimately what kind of stories appear in all forms of media. The government also reserves the right to single out any individual who it considers “deviant,” “revisionist” or “reactionary.” Since the journalist card expires every five years, MIC can also revoke the card at any time.

Losing the “journalist” status in Vietnam might not necessarily exclude one entirely from journalism activities. However, it bars one from any career progression, as one must have the journalist card to work as an independent representative reporter or hold a managing position within a news agency (Article 22 and 23). It also strips one of important journalism capacities, such as field work investigation or the ability to contact competent authorities or participate in court trials (Article 25).

These are the powers that no government should have over its journalists.

More importantly, this legal definition of “journalist” obviously excludes independent journalists and citizen journalists. It means that these actors, despite their constitutional rights and their public contributions, will always act outside the law. Hence, their activities can be denounced as unlawful anytime the authorities wish.

On a larger scale, the arbitrary government control of journalists also extends to their rights to freedom of association and right to freedom of employment.

The Association of Journalists of Vietnam, as set forth in Article 8 of the Law on the Press, is the only recognized organization that is allowed to represent journalists collectively to protect their rights, provide expert opinion on journalistic work upon the government’s request and, most importantly, draft and oversee a journalist’s general code of conduct. The association, indeed, is controlled by the Party, has Party cells, and is managed by the Party, like every other organization that is a branch of the Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP).

On the other hand, news outlets, newspapers, journals, and news agencies in general can only be established by the Party, state agencies or political – social – professional associations (Article 14), all of which are also controlled by the Party. This creates another layer of internal control over licensed journalists.

A front cover of an issue of Communist Journal. The journal solely serves the purpose of promoting communist ideology and barely gets any public attention. Yet, it has received a considerable amount of state funding.

The contemporary situation of the journalist profession in Vietnam

The Vietnamese government often boasts about its commitment to press freedom. For instance, Voice of Vietnam insists that Vietnam has ensured the development and freedom of the press.

The evidence, it said, includes:

- The fact that Vietnam now has 859 print newspapers, 135 online newspapers, 258 websites, and 67 radio and TV stations.

- Also, there are 75 foreign TV channels broadcasted in Vietnam, including CNN, BBC, TV5, NHK, DW, Australia Network, KBS, and Bloomberg. Twenty foreign press agencies have offices in Vietnam, and newspapers in foreign languages are widespread.

- Vietnam is one of the leading countries in the region in the development of the internet and social networking. Vietnam has 35 million Facebook users, which is about one-third of the population.

However, those numbers alone do not reflect the full reality of the lack of freedom of press in the country.

First and foremost, despite a high number of news outlets, the existence of all of them depends on the will and the supervision of the one and only editor in chief, the VCP, as Vietnamese say. Some of them might even be mere “filler agencies,” which means that they were only created to extract state funding for special interest groups, and barely contribute anything to the current landscape of domestic journalism.

Other bigger press agencies are under the complete control of the Party via State mechanisms.

For instance, just in 2018, Tuoi Tre Online Newspaper was suspended for three months and was fined hundreds of millions of Vietnam dong for simply “misquoting” the late President Tran Dai Quang, who allegedly said that he supported the issuance of the Law on Demonstration as soon as possible (the authorities insisted that he did not support this).

In 2019, investigative articles by Phu Nu Online, targeted the land development conglomerate Sun Group, which upset the national leadership since the group has ties with many interest groups within the government. Phu Nu was quickly suspended for one month and forced to issue a public apology to the conglomerate.

After the large exodus of Vietnamese in 1975, there was a joke in Vietnam that “If electric poles had legs, they would leave Vietnam too.” Just last month, Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc joked that “If electric poles had legs, they would leave America to live in Vietnam,” attracting national attention and making headlines around the country. In a matter of hours, the Party was able to force these newspapers to remove their articles about the joke.

Furthermore, the number of foreign TV channels broadcast in Vietnam can be misleading. The content of all of these channels is previously-censored by the MIC, and any deviant behavior can be punished immediately by revoking an organization’s television licence.

And, even if Vietnam is one of the leading countries in the region in the development of the internet and social networking, internet users in Vietnam are also one of the most vulnerable. Our 2019 report on Political Prisoners and Activists at Risk in Vietnam highlights how easily online commentators and social media users can be jailed just for speaking their mind or criticizing the government or local officials.

A brief history of crackdowns against journalists

A brief look into the history of crackdowns against either licensed or independent journalists in Vietnam after 1975 will explain the contemporary situation of the profession.

The first-ever systematic crackdown against licensed journalists in Vietnam started immediately after doi moi, free-market economic reforms launched in 1986, and continued throughout the 1990s.

The delivery of economic liberalization promises seemed to trick people, especially journalists, into believing that reform in the information and communication industry could be possible under the overseer of current Secretary-General Nguyen Van Linh. It did not go as they expected.

The first test was the case of Vu Kim Hanh, the editor in chief of the prominent Southern newspaper Tuoi Tre (“The Youth”). Tuoi Tre, as the leading news outlet in Vietnam, tried to experiment with the so-called openness of the new environment.

Hanh allowed articles on the private life of Ho Chi Minh to be published, which revealed that he did not ascend to the “sainthood” that state propaganda usually attributed to him, and that he had wives and kids too. On another occasion, after visiting North Korea, Hanh wrote an op-ed that called the life of North Koreans “robot-like,” and said that Kim Il Sung’s regime was “despicable.”

Hanh was charged with “slander,” but survived the trial thanks to her husband’s still very strong connections within the Party. Nevertheless, she was completely removed from the journalism scene in the country.

At that point, the crackdown continued when the editor in chief of Sai Gon Giai Phong was forced to resign due to the liberal direction of the newspaper, and when many other small publications were closed down for not meeting the Party’s requirements.

While this crackdown stripped Vietnamese journalists of the right to pursue truth counter to the VCP’s version of history and public policy, the crackdown against journalists after the Project Management 18 Unit (PMU18) corruption case is a reminder that they are not even allowed to use their profession to expose corruption.

PMU18 is a significant corruption scandal which involved the directors of PMU18 and several other ministerial-level officials. Initiated by Tuoi Tre and Thanh Nien journalists in 2005 and 2006, the investigation not only dug deep into the wrongdoings of these officials in managing the State budget, embezzlement, bribery, nepotism, and gambling, but it also exposed their extravagant and immoral lifestyles and how they got away with it.

It was a shocking revelation to the Vietnamese public as it found out how limited economic success after WTO integration had enriched Party members. What probably began as a political conflict within the Party before the national congress, the scandal turned into a sensitive topic since it challenged the VCP’s ability to keep its high-ranking officials in check. The detailed investigation presented to the public was undesirable, and someone had to pay the price.

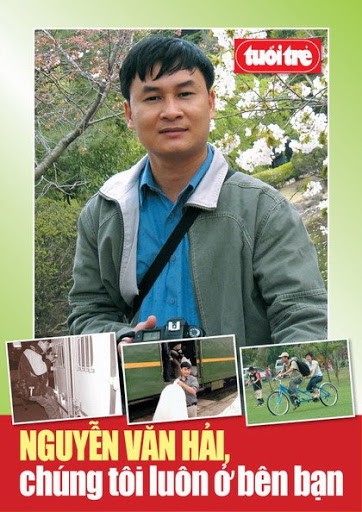

In 2008, two years after the PMU18 case, the “revenge” against involved journalists began. Considered the biggest crackdown against journalists in contemporary Vietnam, over 20 individuals were summoned and interrogated, including the powerful editors in chief of Tuoi Tre and Thanh Nien; eight journalist cards were revoked and two journalists were sentenced to prison. This incident put an end to Vietnam’s investigative journalism concerning corruption and explains why you can barely see any of this kind of corruption reporting anymore without the direct approval of the Party and the Ministry of Public Security.

Tuoi Tre’s tribute to Nguyen Van Hai on a journal cover. Hai was one of two journalists jailed over PMU18’s investigative articles.

During the 2000s, while the government successfully tamed the role that journalists have to play, the development of information technology created a new generation of journalists – independent journalists and political bloggers. These sources have become extremely popular and reliable, and names such as “Anh Ba Sàm” (Nguyen Huu Vinh), “Điếu Cày” (Nguyen Van Hai) “Người Buôn Gió” (Bui Thanh Hieu), “Cô Gái Đồ Long” (Nguyen Le Huong Tra), “Phạm Đoan Trang,” “Mẹ Nấm” (Nguyen Ngoc Nhu Quynh) were highly regarded as independent news sources.

However, since these were separate efforts by different individuals, their works were easily tracked down and suppressed by the government. Only Pham Doan Trang continues to be an active figure with her role in Luat Khoa tap chi and the Liberal Publishing House, which she resigned from recently, but she remains at risk of harassment and arrest, and currently lives in hiding. The rest of the first generation of independent bloggers and journalists were convicted, imprisoned, and/or either still in prison or exiled or forced to live in silence in Vietnam after their release.

***

The ongoing crackdown against independent journalists such as Truong Duy Nhat, Le Anh Hung, and especially the members of the IJAVN, including Pham Chi Dung, Pham Chi Thanh, and Le Huu Minh Tuan, show that the government has never given up its quest for the total control of the media in Vietnam. It will make sure that the collective efforts of either licensed journalists or independent journalists must be punished by any means, regardless of the platforms that are used. With the concentration of online activities on a few major social media platforms, such as Facebook, and the fact that leading technology companies are becoming more submissive to local governments, little will change in the future for journalists in Vietnam under the current regime.

More importantly, this makes any promises by the Vietnamese government concerning freedom of expression (such as in 2019 UPR Recommendations no. 168 and no. 184 and journalist protection such as in 2019 UPR Recommendation no. 172) potentially meaningless. Thus, it is important that the international community and influential NGOs continue to advocate for the abolishment of state-controlled journalism in Vietnam. This could be accomplished by allowing the establishment of representative offices of international journalist organisations such as The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) or Reporters Without Borders (Reporters Sans Frontières – RSF) and recognizing local independent journalist associations.

© 2020 The 88 Project