Incidents Against Freedom of Publication in 2018-2019: How Vietnam Continues to Violate Its Constitutional and International Obligations

How Vietnamese Law Restricts Freedom of Publication

Article 25 of Vietnam’s 2013 Constitution asserts that citizens have the right to speak freely, to have a free press and to access information. Regardless, a thicket of laws and regulations tightly circumscribes freedom of publication in Vietnam.

These restrictions derive in particular from the Law on Publication 2012 and its detailed decrees and circulars. Several provisions of the Law effectively bar the actual realization of Freedom of Publication in Vietnam. These include:

“Subsidiary requirement” (Articles 12, 16): A publishing house can only be established under the aegis of particular state-controlled entities: provincial government agencies, political organizations (which means the Communist Party) and political-social organizations/central public service units, central political-social and professional organizations. The publishing houses can be operated either as a public service unit or a state-owned enterprise, but are necessarily directed by the mother organizations. This implies that no private entities or individuals can ever lawfully participate in the publishing industry.

“Licensing bureaucracy”: Contrary to many other countries, including the United States, United Kingdom, India, and Japan, the licensing procedure for publishing houses does not follow the normal business registration process, but is supervised by MOIC, the Ministry of Information and Communication (Articles 12, 22). The formation of a publishing house also has to be in accordance with the “general plan” of the Ministry. Technical barriers are numerous, such as a requirement that a publishing house have at least five editors who have been licensed by MOIC to practice “editing jobs” (Article 13, 18, 19, 20). Printing companies, wholesalers, and bookstores, as well as importing and exporting companies, are required to adhere to the registration procedure and requirements of the Ministry (Articles 31, 32, 36, 37, 39).

“Appraisal and censorship”: By controlling all of the inputs of the publishing industry, the Vietnamese legal environment reduces greatly the risk that “deviant” ideas and concepts may appear in national publications. And, just in case some slip through, appraisal and censorship are utilized to deal with these issues.

Self-censorship: Articles 18 and 19 require the management of each publishing house and other related businesses decide if the content of a specific book may be unlawful, a difficult task because the relevant laws are vague and arbitrary (Articles 18, 19).

Appraisal subsequent to a complaint: MOIC or a provincial People’s Committee can intervene and re-appraise if they receive information saying that a particular book or publication is inappropriate and can be unlawful (Articles 6, 35, 40).

Automatic appraisal: Certain books and compositions are automatically appraised, either by the publishing house or the experts of the Ministry. They include: (1) Any book and document published before 1954 in areas under the control of the French colonial authorities; (2) Any book and document published from 1954 to 1975 in southern Vietnam that was not endorsed by the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam ; (3) Books or documents published abroad (Article 24).

Incidents Against Freedom of Publication: 2018-2019

With the legal constraints described above, it is understandable that the publishing industry, authors, and readers in Vietnam are deprived of their autonomy. The current situation is not so bad as it has been in the past, for example in 1975, after the surrender of the Saigon-based Republic of Vietnam, when hundreds of millions of books were burnt in a campaign to “eliminate depraved and reactionary culture.” However, plenty of recent incidents illustrate how the regime suppresses the fundamental right to publication in peacetime. Generally speaking, the authorities employ two approaches to deal with what they call “dangerous elements” in the publishing industry.

Firstly, books, authors, and publishing houses that attempt to publish outside the purview of the authorities usually face harassment or confiscation of the published works.

Although there are administrative measures that the regime can use to suppress unlicensed publishers and publications, it tends to rely on informal methods to intimidate them. According to Degree 159/2013/ND-CP, people establishing a publishing house without permission or publishing unlicensed publications may be fined from 70 million to 100 million VND (approximately 3000 to 5000 US dollars). This fine, however, is not effective although it is a significant amount compared to Vietnamese average income, and the independent publishers usually operate in a covert manner. Hence, terrorizing and intimidating the authors and anyone involved in the publication process (even those participating in printing or delivering the materials…) until they give up their participation seems to be the more “appropriate” way in the view of Vietnamese authorities.

In 2018, independent journalist Pham Doan Trang was arrested and interrogated for the publication of her unauthorized book“Politics for the Common People.” Published on Amazon, Smashwords, and Luat Khoa, it is a well-received publication in the blogosphere and in print abroad. Nevertheless, such a publication will never obtain a permit to be printed, published, or circulated inside Vietnam. Efforts to send printed copies of the book to Vietnam from abroad were halted as the books were confiscated by the customs. While it is safe to say that the book should be considered a standard academic publication, helping readers to understand and explore politics, government models, democracy, and political interactions, its discussion of Vietnamese political incidents and situations makes the book unacceptable to the authorities. Nonetheless, Pham Doan Trang and her publisher, Freedom Publishing House, still make an effort to publish her books in print in Vietnam and distribute them via their network of supporters. For Trang, printing books like hers inside the country is the manifestation of the resistance spirit against the dictatorship in Vietnam. What the government prohibits, they will do.

Pham Doan Trang and her books in Vietnam. Source: Pham Doan Trang Facebook

Similarly, in 2019, the bank accounts of the Freedom Publishing House (FPH), an independent publisher formed in February 2018, have been shut down and its delivery persons harassed. FPH’s latest publications include A Handbook for Families of Prisoners, paperback reprints of the famous Politics for the Common People, by Pham Doan Trang, and Lives behind Bars, by Pham Thanh Nghien. FPH management told the Voice of America that “there’s nothing unusual about the regime’s attacks; it would do the same to any publisher that operates outside the system of state censorship.”

Author Pham Doan Trang told Radio Free Asia (RFA) that when 1000 copies of her book “A Handbook for Families of Prisoners” were given away to readers in Vietnam, many secret agents pretended to be interested in the book and made appointments at hidden locations to grab and beat the persons who delivered them.

The situation is not appreciably better for lawful publishers and licensed publications.

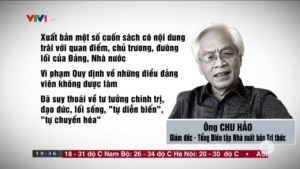

VTV1 reported on the decision of the Central Inspection Commission against Professor Chu Hao, announcing it would discipline him for publishing books, articles, and statements with “contents contrary to the views and policies of the Party and State.” Source: VTV1

The most notorious recent action against lawful publishers is the case of the Tri Thuc (“Knowledge”) Publishing House, which was under the management of Professor Chu Hao, a well-respected progressive intellectual. Solely for publishing translations of Western political classics – books, for example, by Frederic Bastiat (The Law), Friedrich Hayek (The Road to Serfdom), and Peter Singer (Karl Marx), Professor Hao was condemned as a revisionist by a Communist Party tribunal and expelled from the Party in October 2018.

Or consider the translation of Benedict Anderson’s “Imagined Communities” by Luu Ngoc An, which was informally published and circulated via social media, allegedly under the aegis of the Institute of Cultural Anthropology, only to be criticized by the ultra-conservative communist website “Loa Phuong” as “reactionary” and “against the policies of the Party and State.” Nguyen Van Son, representative of the Institute, as well as a member of the state-sanctioned Association of Vietnamese Writers, denied that the Institute of Cultural Anthropology published the book. Yet, according to our sources, Mr. Son was still suspended from his job for a while, and he has been prohibited from editing books published by the Association of Vietnamese Writers. The story behind the publication of the book remains unclear, but the punishment imposed on those who were deemed to be involved with the publication of a book that the authorities don’t like was straightforward.

Not only books about Western philosophy or with political content face censorship. Historical books and investigative works concerning domestic problems can be targeted, too.

In 2018, a book, Gạc Ma – Vòng Tròn Bất Tử (“The Immortal Ring of Gac Ma”), which told the story and the historical context of the Gac Ma Battle (known internationally as the Johnson South Reef Skirmish) between Vietnamese naval forces and Chinese counterparts, was withdrawn from the market for “incorrect information” and has yet to be re-published. The public, however, understands that this is a political move to censor information on the modern historical conflict between Vietnam and China.

Singer Loc Vang and his biography. Source: motthegioi.vn

In the same year, “Song of Destiny: The Biography of Loc Vang” was suspended from circulation pending further appraisal by the Ministry of Information and Communication. This was a transparent ploy to recall and censor a story about the terror against artists in Vietnam before 1975. (Loc Vang, a famous singer in Northern Vietnam, was convicted and spent eight years in prison just for singing songs created by Southern composers.)

In 2019, the investigative report “Windy Island” was recalled for “revisions,” very possibly permanently. Looking deeply into the horrific life of the first HIV-positive patients in Vietnam, how AIDS victims faced their deaths, how underage children were sold for sexual activities, and the lives of Vietnamese prostitutes and prisoners, the book paints a cruelly realistic picture of the life of many Vietnamese, highlighting inequality. Too realistic to be deemed acceptable by the “people’s government” of Vietnam.

“Windy Islands.” Source: tienphong.vn

Freedom of publication in particular, and freedom of the press, in general, have never been respected in Vietnam. Even so, during the 30 years from 1986 to 2016, a period characterized by rapid economic reform and deepening international integration, a new generation of writers persistently tested the boundaries of the permissible; many were successful. Overall, freedom of thought and academic independence grew substantially during this period. However, others, like social and political critics Le Cong Dinh and Cu Huy Ha Vu, were severely punished for daring to challenge the Communist Party’s monopoly of political power. The rise of some now-prestigious publishers, such as Dr. Chu Hao’s Tri Thuc, was largely thanks to the openness of the new economy and the more liberal legal frameworks adopted when Vietnam negotiated membership in the World Trade Organization.

The consolidation of Nguyen Phu Trong’s power since 2016 has reversed most of these developments. Two months after Trong stabilized his position as the Vietnamese Communist Party’s top leader in 2016, internationally-renowned journalist Anh Ba Sam (Nguyen Huu Vinh) was sentenced to five years in prison. From that point on, the purge against independent thinkers, activists, and journalists quickened and still shows no sign of ending.

Why Vietnamese Law Violates International Law on Freedom of Publication

Freedom of publication is not explicitly recognized as a separate right in international instruments concerning human rights. However, freedom of expression is understood to include the right to freedom of publication.

Article 19.2 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) clearly states that“Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.” The freedom “to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds” can never be achieved if the state controls the access to publication.

The Vietnamese government argues that it is utilizing the exceptions provided in Article 19.3 of ICCPR. Yet, to prevent a free speech practice that can harm national security or public order, the ICCPR requires that such speech must be presented and examined in a professional manner. The Vietnamese government has, however, relied on barriers of subsidiarity and license to prevent the introduction of independent elements into the publishing market, a “prior restraint” technique that perverts the intentions of ICCPR exceptions.

Nor is the Vietnamese government’s appraisal process based on the standards of ICCPR. The threshold of “national security and public order” in Vietnamese laws is already arbitrary and subjective (specifically, it does not adhere to the Siracusa Principles or the General Comment No. 34 of the UN Human Rights Committee). Further, because the regime bans the circulation of published works anytime that these publications are deemed to reflect the ugly or unjust aspects of the country, the Ministry of Information and Communication shows that there is nothing inherently damaging to the national security or public security about these publications that motivates its actions, but rather the regime’s intention to depict and narrate all aspects of public life.

At a January 2019 session of the Universal Periodic Review of the UN’s Human Rights Council, the Vietnamese government solemnly renewed its human rights commitments. Unless it revises its administrative and legal practices to enable true freedom of publication, this was an empty promise to the international community. Will it, this time, actually “abolish prior censorship in all fields of cultural creation and other forms of expression, both online and offline,” as it has agreed to in accepting UPR recommendation no. 194, among others?

If so, Vietnam’s government should begin by revising the Law on Publication to relinquish its control over publishing houses and the content of published works, prior to and after publication.

© 2019 The 88 Project