Vietnam Free Expression Newsletter No. 28/2022 – Weeks of July 11-31

Greetings from The 88 Project. We bring you news, analysis, and actions regarding human rights and civil society in Vietnam during the weeks of July 11-31. The highly unusual case of Bong Lai Temple continues to dominate the news cycle and social media, with serious implications for Vietnam’s current legal framework. One blogger was sentenced to years in prison while another went on strike to protest harsh prison conditions for political prisoners. Protesters in Nghe An Province alleged physical abuse and forced confessions; several villagers were later criminally charged. Attacks on non-state controlled churches continue unabated even as the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom calls out Vietnam’s violations in its latest report, and the UN Human Rights Council condemns Vietnam’s willful dismissal of its recommended changes. Human trafficking has also become a thorny problem as Vietnam is added to the U.S. State Department’s blacklist. However, geopolitical considerations by the United States as it tries to contain China could give Vietnam more leverage and less concern about retaliation for human rights violations. Basic freedoms will be in even more danger as Vietnam transitions to the digital age with communication platforms such as Zalo, compounded by electronic ID cards and smartphone apps that can track citizen movement and activity. Read our midyear report on Vietnam’s political prisoners.

HUMAN RIGHTS & CIVIL SOCIETY

Political Prisoners

The six temple members at trial on July 20, 2022, Source: State media via RFA

The Bong Lai Temple case has taken an even stranger twist. After six of its members – allegedly forced to confess under coercion – were sentenced earlier this month to a total of more than 23 years in prison for “abuse of democratic freedom,” another member has also been charged. Le Thu Van, 67, is going through her last-stage cancer treatment and is not expected to survive. Nonetheless, a warrant was issued for her arrest. The group’s lawyers helped bring the severely ill Thu Van to court and got permission to bring her back to the hospital.

The lawyers also were able to post bail for the 90-year-old head monk, Le Tung Van, something never seen before with political prisoners. Le Tung Van was sued by the monk Thich Nhat Tu from the state-controlled Buddhist Church of Vietnam for “defamation” and “sacrilege.” Nhat Tu did not show up at the trial. Le Tung Van testified that he never belonged to the Buddhist Church of Vietnam and thus argued that its rules do not apply to his temple. Le Tung Van said further that his freedom of faith and religion were being violated. The monk’s lawyers announced that their client has appealed the verdict and will countersue.

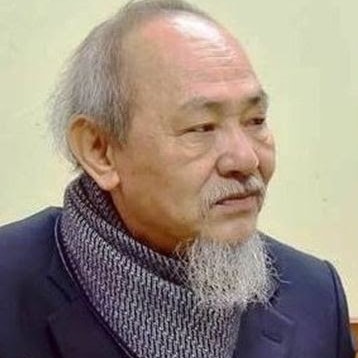

Nguyen Duc Hung

Nguyen Duc Hung was sentenced on July 13 to five and a half years in prison for “anti-state propaganda” in an “open trial” that his family did not know about until they read about it in the newspaper. According to a well-known lawyer, Vietnamese laws only require the state to notify a defendant’s lawyer, not their family, of the trial date. It is not clear if Hung had a lawyer at trial. An activist who once participated in protests against the Formosa environmental disaster in 2016, Hung was convicted for his social media posts on a wide range of subjects: land rights, human rights, public health, and corruption.

Nguyen Ngoc Anh, a blogger currently serving a six year prison term at Xuan Loc Detention Center, has launched a short protest to demand better conditions for political prisoners. According to his mother, Nguyen Thi Chau, “Most of the prisoners jailed at Xuan Loc on political charges are now held in small, humid cells and suffer from poor health, though better cells are available in a new wing of the prison.”

Five women and two men from Nghe An Province were arrested last week for clashing with riot police as they demonstrated against the demolition of a village road. Four of the protesters have been charged with “obstruction” and the rest with “disturbing the peace.”

This week, we think of the birthdays and arrest anniversaries of the following political prisoners:

Pham Chi Thanh and Nguyen Trung Truc

- Journalist Pham Chi Thanh, birthday August 2, sentenced to five years and six months in prison for spreading “anti-state propaganda”

- Member of the Brotherhood for Democracy, Nguyen Trung Truc, arrested August 4, 2017, and sentenced to 12 years in prison for “subversion”

- Activist Le Van Phuong, tried on August 2, 2019, and sentenced to seven years in prison for conducting “anti-state propaganda”

Activists/Community at Risk

Nguyen Xuan Mai, a representative of the Cao Dai Buddhist Church, was detained for six hours at Tan Son Nhat Airport after returning from Washington, D.C., where she attended the International Religious Freedom Summit.

International Advocacy

Pham Doan Trang

The Committee to Protect Journalism has announced that Pham Doan Trang is one of four journalists who will receive the International Press Freedom Awards, to be honored in New York City on November 17, 2022.

The United States Commission on International Religious Freedom has issued its Vietnam report. Among the many recommendations is to monitor government actions against “unregistered religious organizations” – the recent Bong Lai Temple case is a perfect example.

The International Federation for Human Rights has delivered to the UN Human Rights Commission (CCPR) a scathing condemnation of Vietnam’s utter failure to enact any of the key recommendations made by the Commission: “The Vietnamese government’s submission, received by the CCPR on 29 March 2021, contains a profusion of plans, roadmaps, studies, workshops, and reports that seem to be aimed solely at vindicating the government’s adherence to a restrictive national legislative framework that is totally incompatible with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).”

The U.S. State Department has released the 2021 Trafficking of Persons Report on Vietnam.

NEWS & ANALYSIS

US Adds Vietnam, Cambodia, Brunei to Human Trafficking Blacklist. Sebastian Strangio, The Diplomat; July 21, 2022: Human trafficking worsened considerably in Southeast Asia in 2021, with the United States government adding Vietnam, Cambodia, and Brunei to its trafficking in persons blacklist and downgrading Indonesia. In this year’s Trafficking in Persons (TIP) report, released on Tuesday, the U.S. State Department scrutinized 188 nations’ efforts to halt human trafficking and punish those responsible. The report sorts nations into three tiers, with its lowest grade – Tier 3 – reserved for “countries whose governments do not fully meet the minimum [anti-trafficking] standards and are not making significant efforts to do so.” In this year’s report, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Brunei were both dropped down to Tier 3, while Indonesia was lowered from Tier 2 to the Tier 2 watchlist.

Vietnam’s Ecological Leninism. David Hutt, The Diplomat; July 14, 2022: Environmentalism provides an umbrella. It cuts across class – the poor farmer and the billionaire will be equally impacted by climate change – and across geography and generational lines. And it has created new bridges between individual activists, the wider public, and the burgeoning civil-society groups. … Naturally, the VCP is concerned. For sure, it rules over one of the most repressive states in Southeast Asia. But it does often have to listen to public complaints. A noteworthy example of this came when the Hanoi city authorities backed down to public protests over the city cutting down trees. Vietnam’s Western allies are used to turning a blind eye to its repression of factory workers or lawyers. But the United States and European Union have made much noise about Hanoi joining their climate agendas. Their response to [Nguy Thi] Khanh’s imprisonment was more critical than usual.

Vietnam’s Zalo Connect app: Digital authoritarianism hidden in peer-to-peer aid platforms. Trang Le, Global Voices; July 20, 2022: Zalo Connect illustrates how digital humanitarianism can function as a form of digital authoritarianism, legitimising an extractive relationship with the very groups they seek to assist, by requiring a public disclosure of miseries. Difficult questions need to be asked. What problems and solutions are being framed for us? Who benefits from this framing? What does it mean for how we calibrate vulnerability, aid, and protection? Against the context of persistent failure from the state to provide a safety net to its citizens, Zalo Connect’s design implies a transactional solution to a structural crisis: The donor sends necessities and the problem is solved. But the problem of providing basic goods cannot be demoted into a mere problem of matching supply and demand.

You Are Being Watched: What Happens To A Vietnamese Citizen’s Chip-Based ID Card In 2022? Lee Nguyen, The Vietnamese; July 26, 2022: Vietnamese citizens should also worry about this type of electronic identity account when it is installed on their smartphones. Verifying their identity via an e-ID account will most likely result in the app requesting permission to access the camera. In addition, smartphones are storage devices with abundant personal information, location tracking, video and voice recording, and internet connection. These gadgets make tracking people’s movements and accessing their personal information very simple. In July 2021, Haaretz Newspaper in Israel reported that the Vietnamese MPS purchased a software program used to infiltrate people’s smartphones from the technology company, Cellebrite.

IN CASE YOU MISSED IT

Read our midyear report on Vietnam’s political prisoners. In the first six months of 2022, there were 15 new arrests, and 18 activists were convicted at trial. Six were given prison sentences of five years or more.

TAKE ACTION

Dang Dinh Bach

Dang Dinh Bach is an environmental advocate sentenced to prison for five years for “tax evasion.” Watch our translation of a speech he gave before his arrest, in this video, “Dang Dinh Bach in his own words: how I became an environmental advocate,” available with both English and Vietnamese subtitles.

© 2022 The 88 Project