Vietnam’s BOT Dilemma: Activists at the Gates

The anti-Build–Operate–Transfer (BOT) movement is one of the biggest movements in Vietnamese civil society during the first two decades of the 21st Century. Beginning in 2017, public dissatisfaction with oddly placed BOT toll booths began to grow and the movement gained momentum when professional drivers, everyday road-users, and the local residents realized how lucrative and abusive the BOT business was. For example, in 2018 alone, the revenue of only 57 BOT projects was 12 billion dong (approximately US$500 million). In particular, the BOT project expanding national road No. 51, connecting Ho Chi Minh City and Vung Tau, earned 750 billion dong that year, amounting to 2 billion dong every day.

This report aims to highlight the problematic legal framework of BOT projects, how the system is prone to corruption, and the importance of the 2018 BOT protest movement.

BOT: A corrupted reality

BOT is a form of project delivery method, usually for large-scale infrastructure projects, wherein a private entity receives a concession from the public sector to finance, design, construct, own, and operate a facility stated in the concession contract.

In Vietnam, the Law on Public-Private Partnership Investment (PPP Law), issued in 2020 and effective starting in 2021, is the primary document regulating BOT and other types of PPP investment. However, prior to this law, PPP investment had been codified and usually stipulated by governmental decrees such as Decree 62/1998/NĐ-CP, Decree 63/2018/NĐ-CP and circulars (legislations) issued by the Ministry of Transport (MOT). Even without the already weak check-and-balance system in the National Assembly, these legislations have always been prone to abuse by group interests and corruption.

A stand-off between drivers, residents, and the traffic police at Cai Lay BOT toll booth. Souce: Nam Thai/TTXVN

There are three reasons why the system is inherently problematic.

First and foremost, while a BOT project appears to provide some advantage in tapping the resources of private sector financing, which otherwise might not be available, the legislation and even PPP Law provide neither a threshold for the building density nor a definition for new project development.

This leads to the commonly abusive practices where a project does nothing more than fix a short provincial road or expand an existing regional road, while claiming to be a megaproject. The erected tollbooths then charge road users an excessive amount of money for an unreasonable amount of time (which can be extended to over 20 years).

The implementation goes against the usual practice where BOT projects are completely separate from public infrastructure and give users a chance to choose between an upgraded, privately-owned option and a public one.

But that is just the tip of the iceberg. The second reason is that, according to Dr. Hoang Ngoc Giao, director of the Institute for Policies on Law and Development (PLD), most of the BOT agreements have secrecy clauses preventing both private and public partners from releasing information about the legal, financial, or technical aspects of the project. This means that no one knows what or how the contractors contribute to national infrastructure or why the toll fees are implemented in certain ways.

And thirdly, the process of bidding, appraising, negotiating, and signing contracts is also confidential, as no one knows when an authority appoints contractors. There is no public advertising, formal bidding information, or even notice of solicitation of proposals. The MOT has eliminated competition in terms of quality, capacity technology, and cost-effectiveness. In short, the process is rife with corruption.

The 2018 national movement: a wake-up call

The ubiquitous construction of toll booths and the introduction of road user fees in many regions of the country made residents realize the arbitrariness and lucrativeness of the BOT business in Vietnam. Independent protests against specific toll booths quickly turned into a national movement with thousands of participants. This map (below) shows several locations of BOT toll booths where drivers, local residents, and activists have protested. Just to name a few, we have recorded major incidents at the following toll booths: BOT Bac Thang Long – Noi Bai (Ha Noi), BOT Cai Lay (Tien Giang), BOT Ben Thuy (Nghe An – Ha Tinh), BOT An Suong (Ho Chi Minh City) , BOT Ninh Xuan (Khanh Hoa), BOT Pha Lai (Bac Ninh), BOT Hoa Lac (Hoa Binh), BOT Song Phan 2, and BOT Bo Dau.

The objectives of the protests are usually simple but reasonable.

In some cases, protesters have called for the relocation of toll booths. For instance, in the case of BOT Tan De or BOT Cai Lay (and 16 others), the protesters insisted that the BOT investors did not contribute anything to the road for which they were charging user fees. Instead, they built or fixed other shortcut routes, while the authorities permitted them to reap benefits from busier roads that they’d not actually worked on.

Second, the protesters have attempted to expose the nepotism currently plaguing BOT businesses. One prominent case is BOT Phap Van-Cau Gie. Originally, this old road was built using public funds. However, after one night of asphalt coating, a BOT toll booth was erected and users were charged tolls as if the road had been completely rebuilt. The BOT investor allegedly has a close connection with a public official.

Third, the protesters oppose the unreasonable period for which BOT investors are allowed to collect fees from their toll booths.

The protesters have used all the peaceful remedies they have at their disposal. In most cases, they have tried to contact the local People’s Council and People’s Committee but found out that the local governmental agencies have no authority over BOT businesses. Moreover, filing complaints against national agencies has not provided any meaningful results.

Left with no other choice, activists decided to use the tactics of civil disobedience, including blocking the toll booths, refusing to pay tolls, and causing traffic jams until the toll booths decided to release all the vehicles.

A protest at Ben Thuy BOT toll booth as drivers blocked traffic and displayed a banner saying: “Competent authorities should help their people.” Source

Their strategy worked, with almost all of the protests attracting national attention and gaining near universal support. The most intense demonstrations included the protests against BOT Bac Thang Long – Noi Bai, BOT Cai Lay, BOT An Suong, and BOT Ben Thuy, with large demonstrations and coordinated efforts among drivers and local residents.

On the other hand, BOT projects have been aided by resourceful local authorities. Intimidation, harassment, violence, and ultimately arrest have been used against protesters.

The movement has forced the speedy issuance of the PPP Law as mentioned above, which will theoretically provide a better and more transparent framework for regulating BOT projects and PPP investment in general. But the ultimate effect of such legislation remains to be seen.

A thorough national inspection of the operation of these toll booths was also carried out. In March 2020, the National Audit Office (NAU) announced that 84 BOT projects would be fined a total of over 4,000 billion dong (approximately US $173 million). NAU also reduced the operation leases of these projects by a total of 300 years.

In specific cases, such as that of BOT Tan De (Thai Binh) and BOT Cai Lay (Tien Giang), investors were required to relocate the toll booths.

The price

All things considered, it would be misleading to say that the movement has changed the mindset of the Vietnamese government; the majority of BOT toll booths are still intact. What is worrisome to human rights groups is a surge in the number of citizens arrested simply for demanding accountability and fairness from the MOT. Numerous protest leaders and BOT activists have been harassed, imprisoned, and subjected to inhumane treatment.

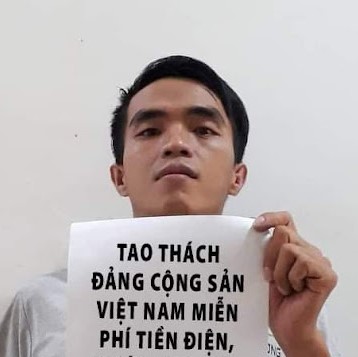

Concerning protests at BOT Pha Lai, seven people, including well-known activist Ha Van Nam, were arrested and later sentenced to a total of 15 years in prison. At least 15 other people have been harassed for their involvement in BOT protests, including nine people who are currently in prison and six who remain free but who are at risk of arrest and further harassment. Of these people, three are women.

Harassment of BOT protesters includes intimidation, administrative fines, physical assault, detention, and property confiscation and/or destruction. Harassment has been perpetrated by public security agencies, as well as individuals and pro-government collaborators. In another recent example, a demonstration against BOT Bac Thang Long – Noi Bai led to the imprisonment of Dang Thi Hue and Bui Manh Tien. The appeal trial was held in July, in which their sentences were upheld but slightly reduced. At a previous protest, Hue was also detained and beaten severely, later resulting in her having a miscarriage. Nguyen Quang Tuy, a driver who participated in the protest against BOT Ben Thuy, was also sentenced to two years in prison (and just released from prison in September 2020).

Dang Thi Hue being dragged by plainclothes public security officers in a 2019 protest. She was later beaten. The encounter resulted in her having a miscarriage. Source

Most of the activists are charged under “disrupting public order,” an arbitrary clause usually employed against peaceful protesters. The trials have angered the public and resulted in the intervention of prominent international organizations. In the case of Ha Van Nam, Amnesty International officially voiced its concerns over the political motives of the case. Even now, during the pandemic, local residents still continue their fight against the allegedly unlawful BOT projects. Just this April and May, residents living in Ea Dar (Daklak) and Ninh Xuan (Khanh Hoa Province) met with local authorities and investors to reach common ground in dealing with BOT projects, but they have not yet succeeded in changing the BOT practices.

***

Overall, we recognize that the national government and local authorities have retreated to compromise and accept certain requests from the public. However, it appears that the government does not want to be pressured to do anything by the public, even if it is for a better legal framework or transparency. With the arrests and trials of peaceful protesters, victories in the BOT movement have been minimal. And while nationwide protests against BOTs are unlikely to happen anytime soon, we expect the legal struggle against individual BOT toll booths to continue, and we will continue to closely monitor the situation.

© 2020 The 88 Project