Crackdown on Freedom Publishing House: Public Security Harassed, Detained Readers And Confiscated Personal Belongings Without Warrant

Featured Image: Ho Sy Quyet and his son. Source: Ho Sy Quyet

The 88 Project discussed the harassment against Freedom Publishing House in our report on freedom of publication 2018 – 2019, and the crackdown seems to have continued in the first weeks of 2020.

On January 3, 2020, Ho Sy Quyet and his family stayed in their flat at EcoPark, Hung Yen. After the doorbell rang and Quyet opened the door, dozens of public security officers violently overran Quyet. They searched the apartment without any warrant and subsequently escorted both Quyet and his wife to the Public Security office of Van Giang District, Hung Yen province. More importantly, they also took his laptop, camera, mobile phones, and many important documents, such as passports, his son’s birth certificate, and the household registration booklet, in addition to bank cards.

Quyet’s family was held for interrogation for hours. Quyet was detained and interrogated for a total of nine hours. The reason for this unlawful and arbitrary intervention was that Quyet uploaded and reviewed several books from the Freedom Publishing House, and the authorities were “suspicious” that Quyet might be a member of this independent publisher. The public security still kept a lot of Quyet’s belongings and property and demanded that Quyet go next Tuesday to continue to “work” with them. As Quyet stated, the investigation unit that directly interrogated him was not from Hung Yen province, but the A02 unit of the Ministry of Public Security, the same unit that was involved in the case of artist Thinh Nguyen.

Recently, a statement by Quyet himself was published online with more detailed information (a translation of the statement is available on The 88 Project’s website). For instance, his wife was threatened that she would be kept at the police station and wouldn’t be able to pick up her son in the evening if she did not cooperate and sign the given papers. He also specified a list of over 20 confiscated items (worth approximately $5000 US dollars), including not only expensive equipment– such as a Macbook Air, a GoPro camera, a full kit of DSLR camera– but also very important identification papers and documents, such as his son’s birth certificate, he and his wife’s passports, and the family’s household registration booklet (a vital paper affecting every living aspect of the citizenry in Vietnam). As of January 9, 2020, the following papers are still being held by the authorities: their registration booklet, marriage certificate, Quyet and his wife’s passports, their son’s birth certificate, Quyet’s wife’s school transcripts, and Quyet’s certificate of completion of the training program “analysis and debate policies” by IPS. This confiscation has no legal basis since the family has not even been subjected to an administrative penalty, let alone a criminal proceeding. But even if there was an ongoing administrative or criminal proceeding, those confiscated documents play no role in the so-called “unlawful” conduct of Quyet, and thus could not not be seized. According to the Law on Administrative Penalty of Vietnam 2012, the papers and documents confiscated must be appropriate and related to the concerned act (usually drivers licence, professional license, etc.). House hold registration booklet, marriage certificate, and birth certificate are not among them. The confiscation of these papers is an unlawful threat and intimidation strategy employed by Vietnamese authorities, as it will severely affect the family’s daily life. For example, to access to the healthcare system for children in Vietnam, the birth certificate is required.

According to Ms Pham Doan Trang, there are over one hundred readers of the Freedom Publishing House that are facing this type of harassment and personal attacks, a desperate attempt to make sure that “independent reading” cannot flourish in the country. Worryingly, Trang also disclosed that many supportive readers have suddenly ended their contact with the publishing house. and the authorities have harassed delivery persons.

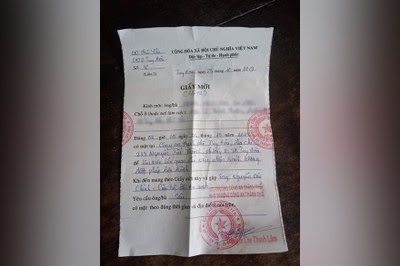

For instance, on October 2019, reader Nguyen Van Khanh, who lives and works in Ha Noi, was repeatedly contacted and asked for his personal information and sometimes “invited” to work with the local public security after ordering the book “Chinh tri Binh Dan,” authored by Pham Doan Trang. His landlord was also “invited,” since she was considered related to the transaction (but she simply received the book on behalf of Khanh).

The invitation given by a local public security to one reader. Source

A representative of the publishing house also told Radio Free Asia that in the first half of October 2019 alone, eight readers were summoned and threatened to be dealt with by “legal mechanism” if they possessed books published by the publishing house.

The current crackdown on book readers is a peculiar development in how the regime deals with civil society and freedom of expression. It is one thing that the regime seeks to restrict independent publishers’ influence by harassing those publishers themselves, but by turning to the readers and harassing them until they give up on independent reading, it is clear that the regime also aims to target freedom of personal thought.

© 2020 The 88 Project