Vietnam in COVID-19: Normalizing a police state?

Vietnam has emerged as a success story in dealing with COVID-19 while the pandemic ravages the globe. With the official report of only over 300 confirmed cases and no fatalities due to the virus, there is little doubt that the authorities have delivered a remarkable strategy and results in containing the spread of the deadly disease, which has already claimed 300,000 lives worldwide at the time of this writing.

Yet, this success story should not eclipse the repressive tactics employed by the Vietnamese government to censor the information on the pandemic. Countries such as Taiwan and the Republic of Korea have also shown their competence to the world with low transmission and low mortality rates. But they did not need to employ repression, the use of force, or the dominance of the public security forces in public activities in order to achieve such results. There are several reasons to believe that the Vietnamese authorities are utilizing the pandemic to normalize the practices of a police state.

The domination of public security forces in the market of public opinion

According to a state-owned newspaper, by March 2020, there were already 700 individuals fined by the security forces for expression related to the coronavirus.

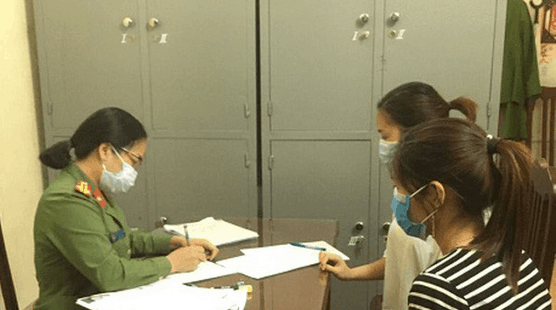

Facebook users being interrogated by local public security agents. Source: Tuoi Tre

A closer look into these cases suggests that most of them involved individuals expressing concerns on social networks, which could have easily been addressed by the government through transparency and intensive information programs to support citizens.

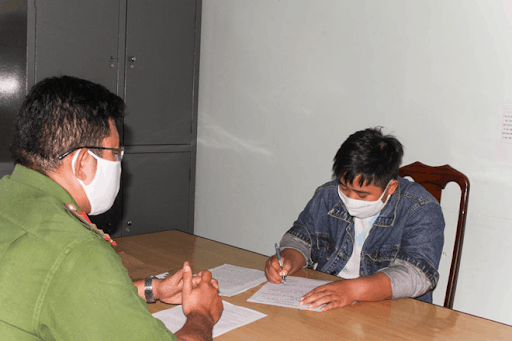

For instance, in Ha Giang Province, three teachers were fined around 10 million Dong (approximately 450USD) for simply saying “The outbreak is out of control!,” along with posting some photographs of Vietnamese patients in a quarantine area. According to the security forces, these posts caused “unnecessary panic” among the public. They also asserted that this was fake news because the photographs were from different provinces, and not Ha Giang.

The teachers were “invited” to work with the local public security. Souce: Phap Luat Online

A doctor in Can Tho was fined for a short status saying, “Can Tho (province) has its first case. The residents should enhance their immunity system by eating more vitamins and mineral-rich food.” The local authorities also announced their first case shortly after.

The majority of online expressions of these citizens were neither dangerous to the public nor damaging to the national effort against COVID-19. Yet, the “perpetrators” were summoned, briefly detained, and interrogated at their local Public Security Bureau offices as if they had committed serious crimes. By free-riding on the public support for the “national unifying cause” of dealing with COVID-19, the authorities justify the excessive and arbitrary involvement of public security forces in public life.

The acquiescence of this practice will continue to undermine the role of public opinion in checking and balancing the already powerful regime, and therefore the right to freedom of expression in the long run.

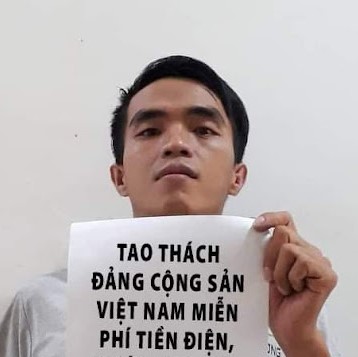

Criticizing the state as a criminal offense

In addition to using public security forces to deter citizens from expressing their opinions online, the practice of punishing online expression with criminal offense has also been utilized by public security to silence criticism of the state during the pandemic.

Ma Phung Ngoc Phu, a resident of Can Tho, was arrested on April 11, 2020. Her crime, allegedly, was asking “There is news that one person has passed away from coronavirus in Vietnam, why do no news outlets talk about this?” in a Facebook post. Other items that were under investigation include her liking several posts of other people criticizing the COVID-19 policy of the state and commenting on these posts. Phu was later sentenced to nine months in prison.

Phu at the security investigating agency in Can Tho. Source

Another victim of this arbitrary practice is Dinh Thi Thu Thuy, who also resides in Can Tho. According to the accusation against her, Thuy had opened multiple Facebook accounts to edit, post, and share thousands of documents defaming and slandering the Party’s leadership. The Public Security Bureau also added that during the “national war” against COVID-19, Thuy had used social media to distort the state’s policy and create confusion among the public. Thuy is currently in pre-trial detention.

In Thai Nguyen Province, the People’s Procuracy officially charged Pham Van Hai under Article 288 the Criminal Code for “illegal provision or use of information on computer networks or telecommunications networks” for similar reasons. On social media, Hai had contended that there have been deaths in Thai Nguyen province due to the coronavirus and questioned the integrity of the official information.

It is difficult to reconcile these arbitrary criminalizations with the legal requirements of international human rights law. The restriction of freedom of expression and related punishments are neither “provided by law,” as required by Article 19 of the ICCPR, nor do they pass the test of “necessity and proportionality,” as explained in General Comment No. 34.

***

As observed by many international scholars, the COVID-19 pandemic gives a unique opportunity to dictators and authoritarian regimes to prove their superiority over the old “liberal democracy” model and strengthen their repressive systems. A brief overview of the situation in Vietnam shows that these tactics contribute nothing to a sound and successful anti-COVID campaign. More importantly, it lowers the threshold even more for both administrative and criminal intervention of public security agents in repressing online expression.

© 2020 The 88 Project