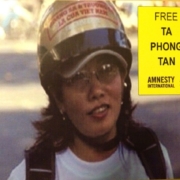

Unending Punishment: Political Repression in Vietnam

Dang Thi Kim Lieng (above, black shirt) self-immolated on July 30, 2012. Photo source: BBC (not used in original article)

Asia Sentinel, July 29, 2017: “On July 30, 2012, the mother of political prisoner Ta Phong Tan burned herself to death at a government building in despair over her daughter’s imprisonment. This is the fifth anniversary of her death.

This is what life is like as a prisoner of conscience in Vietnam: Isolation. Withholding of newspapers and letters from family, denial of menstruation supplies, visits from lawyers, medical treatment and even light. “Prisons within prisons,” an Amnesty International report calls it.

It is brutal before the arrest. The harassment. The intimidation. The black-clothed thugs lingering around your house, stealing your cameras, beating you up, and beating up your friends as well.

It is brutal during the court proceedings. The frustration of a one-day show trial. The lack of impartial news coverage. The outrageous sentences.

It is perhaps most brutal during the three or 10 or even 16 years in prison, serving a sentence under severe conditions, with only rare contact with family and none with friends.

And it is even brutal upon release. There is forced exile, family separation and restrictions on movement. And there is nearly constant surveillance.

Every aspect of the pre-arrest, arrest, detention, trial, and even release of Vietnam’s political dissidents is designed to minimize their contact with the outside world. The Communist regime wants them forgotten. It wants other malcontents to take heed.

The international press lit up when Chinese authorities released Nobel Peace Prize medalist Liu Xiaobo days before his death from cancer. Properly it condemned the tactics Beijing employed against Liu and his wife, Liu Xia, who remains under house arrest. Liu was famous, but not unique. In China and in Vietnam there are hundreds more Lius.

On July 30, 2012, Dang Thi Kim Lieng self-immolated at a Vietnamese government building in a desperate, defiant protest as her daughter awaited trial. Lieng had not seen her daughter, political blogger Ta Phong Tan, since the previous September.

“[M]y sister’s detention and charges affected her deeply,” Ta Minh Tu, Tan’s sister, told Radio Free Asia in a 2012 interview. She also added that: “[The authorities] followed us all the time. Whenever I would go to [Ho Chi Minh City], someone would immediately begin tailing me.”

Many believe that the pressure of the charges against Tan, along with continuous surveillance and threats against the family’s home, drove Lieng to suicide. Tan was sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment that September under Article 88 of Vietnam’s criminal code for her blogging.

When prisoners of conscience are arrested, it is their families that must travel hundreds of miles to bring supplies and news. It is often the families that launch far-reaching international campaigns to free their loved ones, as in the case of Tran Huynh Duy Thuc. Thuc, who blogged on economic and social issues, was convicted in 2010 with three others of ties to an underground political party that the Hanoi regime insists is a terrorist organization. Thuc refused to cop a plea and is now shackled to a 16-year sentence. Though in poor health, Thuc’s father, Tran Van Huynh, continues to campaign tirelessly for Thuc’s release.

The families of Vietnam’s political prisoners must take care of children and elderly relatives orphaned by a long sentence. Young mother Nguyen Ngoc Nhu Quynh, who blogged as Mẹ Nấm (Mushroom’s Mom) was sentenced to 10 years in prison on June 29 because Hanoi deemed her to be spreading “propaganda against the State” under Article 88 of its Penal Code for blogging on topics such as the Formosa environmental disaster and police brutality. Vietnam slammed another mother of two, blogger Tran Thi Nga, with nine years’ imprisonment on July 25 for creating online content related to her advocacy for migrants and victims of land grabs.

Their children may well be adults by the time these mothers are free. While serving time, prisoners miss out on major life milestones. Their parents die and their children grow up while they are the guests of the state. Lawyer Nguyen Van Dai, a civil rights campaigner, was arrested in December 2015. When his father neared death in June, Dai was forbidden to see his father.

Can Thi Theu is a land rights activist. She was arrested September 2016 and is now serving 20 months in prison. In a letter smuggled out to friends, Theu explains the pressures that incarceration in Vietnam’s prisons places on individuals and families alike:

“At 9:00 am on 11 December 2016, I was escorted by the police from the Detention Center No.1, Hoa Lo prison, Hanoi to Noi Bai International Airport. At 11:30am, the plane took off. Looking out the window I saw my hometown, my village gradually fading away. I knew this was the vile revenge of the communist regime against me. They exiled me to a place that is far away from my hometown to traumatize me and to make it difficult and costly for my family to visit me.”

The authorities aim to limit family interaction. They often do not notify families of transfers from prison to prison. Sometimes they are transferred to facilities in remote, hard-to-reach areas. If family members at last arrive to meet their imprisoned loved ones, they may be turned away. They may be required to speak through a monitored phone.

Even after release from prison, life may never return to normal. Le Quoc Quan served 30 months on fabricated charges of tax evasion. Released in 2015, Quan was threatened by thugs at his private home just last month. Their message was grim: “You should focus on your family and try to protect your growing daughters; otherwise we will cause harm to them.”

Pham Minh Hoang, a mathematics professor and occasional blogger, wasn’t tried and jailed. Instead he was stripped of his Vietnamese citizenship and exiled to France. Now, his family is split up; his wife and disabled brother-in-law are trapped in Vietnam and Hoang in France with his daughter.

Exile is a relatively new tactic employed by the authorities. Catholic activist Dang Xuan Dieu has also been exiled to France, and prominent blogger Nguyen Van Hai (Dieu Cay) was exiled to the United States in 2014 as well. Tan, Ms. Lieng’s daughter, was released early from prison in September 2015 on condition that she leave Vietnam for the United States.

Conversely, countless Vietnamese activists and former political prisoners have been denied travel rights at cost to their professional and family lives. In January, former political prisonerPham Thanh Nghien was prevented from travelling to Cambodia, where her father was receiving medical treatment. And in June, Do Ngoc Xuan Tram was barred from leaving Vietnam to visit family as well, due to alleged national security concerns. She is the sister of labor activist and former political prisoner Do Thi Minh Hanh.

All of this separation, humiliation, and pain comes back to a blog post. Or to video clips. Or to a social organization, a land protest, a labor union, or a religious demonstration. It all comes back to people speaking up, exercising their human rights. But despite all of the suffering that ensues from the repression of dissent in Vietnam and elsewhere, many activists continue to fight for the causes that impassion them. And their families? They continue to fight, too.

Can Thi Theu, the land rights activist who wrote the letter introduced above, acknowledges this proudly. Her letter from late 2016 continues on to say:

“But the revenge has completely failed. Just three days after I arrived at Gia Trung prison, my family and landless farmers from Duong Noi flew from Hanoi to visit me. Ms. Tan, Dieu Cay’s ex-wife, also traveled from Saigon to visit me. My family and chi Tan also brought me letters from Father Pham Trung Thanh, from Duong Noi’s landless farmers, and many loving messages from friends near and far, at home and abroad. I am deeply touched and feel so warm in this remote highlands area. Although I am imprisoned, I am not alone, because outside there are thousands and millions of hearts that are compassionate towards the victims of land confiscation like me.

“I know that all of you, Fathers, farmers, and communities, at home and abroad, have given me the confidence and determination to walk the next step on the path that I chose. We are determined to fight together to reclaim the land, the right to life, and the human rights of which the communist regime has deprived my family and those in similar situations.”

For Vietnam’s political prisoners and their families, life is incredibly difficult but hope remains. July 30 is the fifth anniversary of Dang Thi Kim Lieng’s self-immolation. On this date we remember and honor her fiery sacrifice, and continue to work to free prisoners of conscience and to improve the lives of activists everywhere.”

Kaylee Dolen is Content Manager for the 88 Project, a blog that “shares the stories of Vietnamese activists who are persecuted because of their peaceful dissent.”