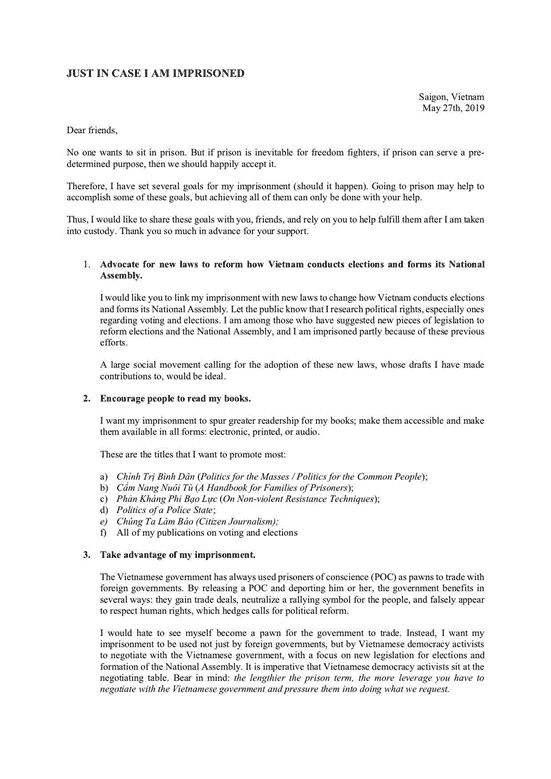

‘Freedom Fighter’ Pham Thi Doan Trang

Pham Doan Trang being taken away during her October 6, 2020 arrest, Source: Will Nguyen

On October 6, 2020, the US and Vietnam had to hold their 24th annual Human Rights Dialogue via virtual sessions due to Covid-19. In virtual attendance were the US ambassador to Vietnam Daniel Kritenbrink from Hanoi, and his counterpart Ha Kim Ngoc from Washington, D.C. According to the State Department’s website, “the three-hour sessions addressed a wide range of human rights issues, including the importance of continued progress and bilateral cooperation on the rule of law, freedom of expression and association.”

No sooner had the meeting concluded than Vietnam demonstrated how far those important objectives were from being achieved. Around 11:30pm that evening Ho Chi Minh City Police, in coordination with Hanoi Police and the Ministry of Public Security, arrested prominent journalist Pham Thi Doan Trang in Ho Chi Minh City and charged her with anti-state propaganda.

A leading voice among human rights activists in Vietnam, Trang is the author of nine books, including one aptly titled “Politics for the Common Citizen”. In 2019, she was awarded the Press Freedom Prize by Reporters Sans Frontières. She is also a co-founder of Liberal Publishing House, an independent publisher that was awarded the Prix Voltaire by the International Publishers Association in June of this year for their audacious effort. Kristen Einarsson, chair of the IPA’s selection committee noted: “The work of Liberal Publishing House in Vietnam as guerilla publishers, making books available in a climate of intimidation and risk for their own personal safety is nothing short of inspirational.”

Taking her bold message of “free and fair elections for all” ever closer to the common person, Doan Trang and her colleagues started the online law magazine ‘Luat Khoa,’ whose aim is to inform and educate readers on legal issues and citizens’ rights. In recent weeks, the magazine has published a series of in-depth analysis of the bloody raid on Dong Tam commune on January 9, 2020, and last month’s highly irregular trial of its 29 villagers. Many people suspect these articles could be a possible reason for Trang’s oddly timed arrest. However, her detention could also be part of a wider crackdown on “troublemakers” as the Communist Party gears up for its five-yearly National Congress taking place in January.

A few months ago, in another Dong Tam related matter, authorities arrested land rights activists Can Thi Theu and her two sons Trinh Ba Phuong and Trinh Ba Tu. After being kept incommunicado for weeks, they and one other land petitioner were eventually charged with “propaganda against the state” for their Facebook posts and live streams about Dong Tam. Trinh Ba Phuong, perhaps anticipating his eventual arrest, even made a video interview to tell his side of the story, or as he put it, “My will, in case I die in prison.”

As for Doan Trang, the government has officially charged her with “propaganda against the state under Article 88 of the 1999 Penal Code.” Technically, this is only applicable to acts committed prior to January 1, 2018, before the law was changed. Today, that same provision, with slightly different wording, is part of Article 117 of the 2015 Penal Code. At this point, we can only assume that the government plans to prosecute Trang not for her more recent activities, however aggravating to them those might be, but for her writings going back several years or more.

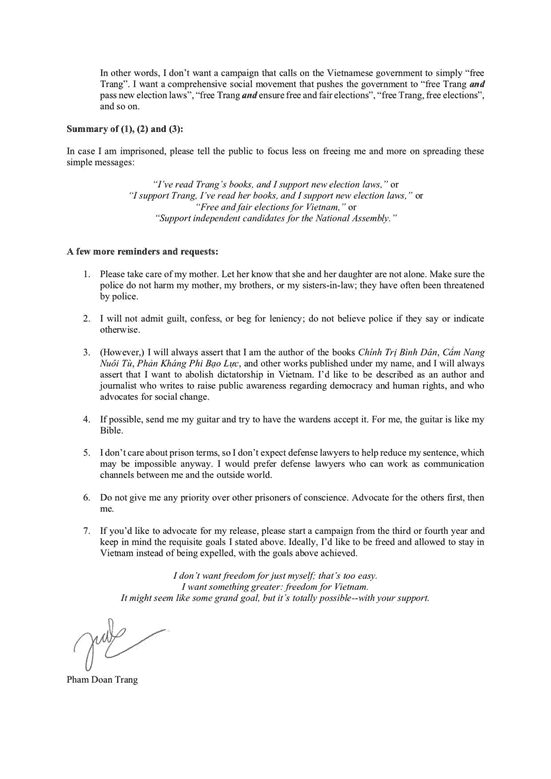

That would not be surprising. In fact, it is probably something she expected. A year ago, Trang had penned a letter titled “Just In Case I Am Imprisoned” (read the full letter, below) and sent it to a trusted friend with specific instructions to publish it the moment she gets arrested. She writes: “I don’t need freedom just for myself, that would be too easy. I want something much greater: freedom and democracy for all of Vietnam.”

Like Trinh Ba Phuong, Trang also made a video before her arrest. In it, she discusses the real possibility of being a political prisoner and of how she rejects being “a commodity” for the regime to barter for trade or other concessions with the free world. She also calls on her colleagues to not “go into silent mode,” but become even stronger and more forceful in her absence.

It is worth noting that Trang has been imprisoned before and is no stranger to the cat and mouse game played by undercover agents. For many years, she was under house arrest and living under constant surveillance. When US President Barack Obama visited Vietnam in May 2016, Doan Trang was invited to meet with him, but security police succeeded in preventing her from getting to the meeting despite her maneuvers. A few years ago, during a street protest against the proposed cybersecurity law, she was physically assaulted by suspected hired thugs who permanently damaged one of her legs; she now walks with a limp. In a dramatic story in the spy-thriller vein, sent to a friend right before she was detained in 2018, Trang describes how several unknown people helped her evade security agents on the streets of Hanoi.

It is not yet clear how long Doan Trang will remain in temporary detention before she is put on trial. According to Vietnam’s loosely-worded Criminal Procedure Code, it could be anywhere from four to twelve months to even more, depending on how the Procuracy evaluates the severity of her alleged offense(s). In the meantime, Trang’s family was finally notified that she had been transferred to the new Hoa Lo prison in Hanoi and that they could send her supplies but would not be allowed to visit. As for her defense, Doan Trang writes in her letter that she does not want any lawyers to argue for a lesser sentence because she is innocent and will never beg for clemency. She requests that the human rights community not demand for her “any preferential treatment over other prisoners of conscience.” But, “If possible, petition so that I’m allowed to have my guitar.”

Featured Image: Doan Trang and her books and guitar

© 2020 The 88 Project