What we demand on International Women’s Day: The right to hygiene pads for women in jail

The 88 Project, March 8, 2017: Blogger Nguyễn Ngọc Như Quỳnh, the well-known human rights defender who has been held incommunicado since October 2016, wrote a note to her mother on the margin of a supply receipt form dated January 1, 2017: “I’ve received everything you sent. I also need shampoo, toothpaste, hygiene pads, and candies.” Yet, as of March 2017, according to fellow female activists who are close to her family, Nguyễn Ngọc Như Quỳnh’s mother has not been able to send her the feminine pads she asked for.

Hygiene pads are not commonly distributed to the women in jail in Vietnam. Former prisoner of conscience Phạm Thanh Nghiên, in our interview with her in 2013, told the story of the struggle of female prisoners to receive adequate menstrual products. While Nghiên was able to receive what she needed from her family, other women had to ask for free feminine pads from their cellmates, or work in the prison to earn money to buy pads from the prison facilities at a much higher price than in the common market. It seems that the distribution of hygiene pads to women prisoners is left to the discretion of specific prison authorities. Some authorities allow the families to send pads, some don’t. Some distribute only cheap, thin, and non-absorbent pads. Some require the women to buy them from the prison’s facilities at an expensive price.

Yet, adequate and free access to hygiene products should be a right for women prisoners. Rule 5 of the United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-custodial Measures for Women Offenders (the Bangkok Rules) on Personal Hygiene explicitly provides for the women prisoners’ free access to sanitary towels:

“The accommodation of women prisoners shall have facilities and materials required to meet women’s specific hygiene needs, including sanitary towels provided free of charge and a regular supply of water to be made available for the personal care of children and women, in particular women involved in cooking and those who are pregnant, breastfeeding or menstruating.”

The free and adequate access to menstrual products for female prisoners is not explicitly mentioned in the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Nelson Mandela Rules), while the men’s need for “proper care of the hair and beard” and to “shave regularly” is addressed specifically. Rule 18 of on Personal Hygiene reads:

“1. Prisoners shall be required to keep their persons clean, and to this end they shall be provided with water and with such toilet articles as are necessary for health and cleanliness.

2. In order that prisoners may maintain a good appearance compatible with their self-respect, facilities shall be provided for the proper care of the hair and beard, and men shall be able to shave regularly.”

Apparently, lack of adequate access to pads and tampons is not only an issue for female prisoners in Vietnam. In America, female inmates are either provided with an inadequate amount of hygiene pads or denied access feminine products altogether. However, there is a difference between the Vietnamese and American situations. In America, criminal justice advocates are free to organize, raise awareness, and take actions to assist the women in jail, including through lobbying lawmakers and bring legal actions in courts. In Vietnam, within the context of a one-party regime, lawmakers and state-sanctioned “social organizations” work for the Party-State; they are not responsive to constituents’ demands. The best course of action is for activists to try to influence the public opinion through raising their voices in social media.

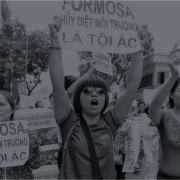

On International Women’s Day this year, a lot of international human rights organizations, as well as Vietnamese civil society organizations, have raised their voices for female prisoners of conscience in Vietnam, and we are thrilled for the international attention given to the women political prisoners. For our part, the 88 Project would like to add our voice to those of Vietnamese female activists and prisoners and their families in demanding the right to adequate and free access to menstrual products for all female prisoners. There should be no political prisoners in the first place, but when women find themselves behind bars for exercising their political rights, they must be treated with decency. This is not too small of an issue to address. Quite the contrary – it is a matter of respecting the dignity of the women prisoners.

If the men in jail can shave regularly, the women in jail must also get their menstrual products freely every month, as much as they need.

© 2017 The 88 Project