Human Rights on the Line: What does Trump mean for US-Vietnamese relations?

With the controversial actions of the Trump administration in the weeks since the inauguration, many are wondering what four years of Trump means for minority groups and the future of the US and other nations alike. The 88 Project explores what impact Trump could have on Vietnam, US-Asia relations, and human rights in the region. Under one scenario, Trump disengages from Vietnam, and Vietnam human rights violations escalate under decreased scrutiny. Disengagement from the US could also mean more regional engagement for Vietnam and China. There is really no scenario under which the US engages Vietnam on human rights for the sole sake of human rights promotion, but a brighter scenario could see the US pushing Vietnam on human rights, even if only minimally, to remind them that other countries are still taking notes– and to provide Trump with domestic leverage. Another possible reality, though, is that regardless of what the US under Trump or any other countries do, Vietnam’s human rights situation will continue on its current course– or worsen.

***

Up until now, the US and Vietnam have been somewhat of “frenemies,” slowly moving past their troubled history together. The warming of their relationship was strong under Obama, perhaps reaching a peak in 2016 with Obama’s visit to Vietnam and ending of the decades-long ban on the sale of US weapons to the country. As lackluster as Vietnam’s human rights improvements were under Obama’s leadership, pressure from international visits and deals has helped publicize prisoners of conscience and environmental issues. But now, Trump’s “America First” rhetoric leave many wondering if Trump will have much of a relationship with or impact on Asia, and Vietnam, at all. In the following sections, we explore the complicated potentials for involvement- or lack thereof- between the U.S. and Vietnam.

The US turning inwards does not necessarily mean it will scratch out the last several years of progress it’s made in courting Vietnam, at least not intentionally. An inward-focused US could maintain friendly ties with Vietnam without being invested in outcomes there, as it is important for both countries to remain allies in their efforts to counterbalance Chinese influence. In fact, despite their outward differences, Vietnam and the US under Trump share many priorities: economic growth, fostering a pro-business environment, and orchestrating a crackdown on institutions and people that allegedly jeopardize national security. In the US, this has been exemplified in Trump’s travel ban and increasingly forceful immigration actions. In Vietnam, this often takes the form of quelling public protest, arresting outspoken critics of the government, and silencing independent media.

However, in his first weeks in office, in addition to his campaign, Trump has said and done very little in regards to Asia except for jab at China on occasion. His only real policy move has been to slash the path for the TPP to move forward, and the State Department’s new Country Report on Vietnam paints a cold, but not dire, human rights situation in Vietnam, with little detail and few voices of those affected. Without trade agreements, a flow of jobs or products, and/or readiness to engage in regional issues, like China and Vietnam’s territorial dispute in the South China Sea, one possible scenario has Trump running from Asia rather than pivoting towards it.

Lack of US ties to Vietnam could have harsh consequences for human rights in Vietnam and other countries in the region, as the sliver of media attention human rights violations received under the Obama administration could be completely extinguished without US pressure. Father Nguyen Van Ly was released from prison just days before Obama’s May 2016 visit to Vietnam. Other releases, like that of Dieu Cay in 2014, have also been speculated to be linked to US pressure. If Trump does not engage with Vietnam on business or security terms, the TPP or the South China Sea, Vietnam will have less of an incentive to improve human rights, even superficially, as a condition for trade, resources, or protection. For example, the US was pushing for stricter labor standards as part of the TPP agreement, but with no way forward for the deal, hopes for better wages and better working protections now lie with the Vietnamese government and corporations- not an international agreement with many eyes upon it.

Furthermore, turning away from Vietnam now could mean that Trump and his administration, as well as the Vietnamese government, lose decades worth of progress in unifying their interests- and arguably more importantly, their civil society groups-including raising standards of living for thousands of people. Any Trump administration cuts to international humanitarian aid, federal funding for international education exchange or technical assistance, or diplomatic visits or inquiries could leave a void that the Vietnamese government is unwilling or unable to fill for its people. This could limit educational and professional opportunities, as well as opportunities for cross-cultural communication and understanding. It could also further stem the flow of news between the two countries and restrict the ability of corporate and nonprofit actors to continue or forge partnerships.

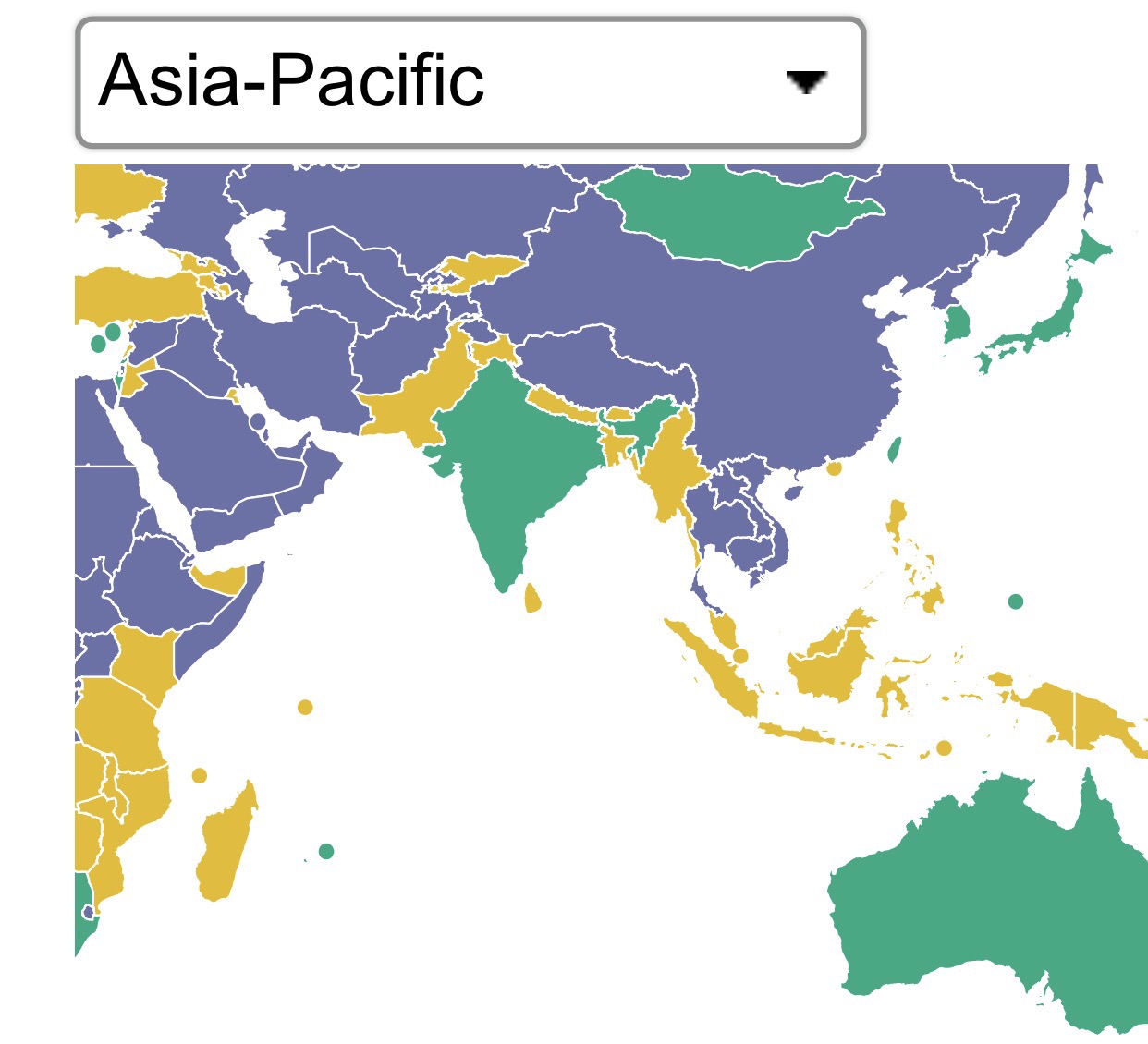

On the other hand, an overly-involved US in Vietnam could surely make matters messy. Take for instance, the possibility that Secretary of State and former ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson could find himself mitigating a dispute he helped create over an energy project in contested waters. However, a US that leaves Vietnam to itself and sets a global tone that it will not intervene to protect citizens from oppressive regimes could also be dangerous. Vietnam was recently ranked “Not Free” in Freedom House’s 2017 report, with a 7/7- the worst possible score- for political rights. Many believe the targeting of activists has increased, as authorities add harassment, assault, and forced exile or restricted movement to its tool belt of repression, alongside formal arrests.

Screenshot of Asia map from Freedom House report, with green indicating “Free,” yellow “Partly Free,” and purple “Not Free.” Source: Freedom House, 2017, Freedom in the World 2017

According to our records, since November 1, 2016, Vietnam has arrested eight activists and extended the detentions of two others. That’s ten major actions in a little over four months. There has also been physical violence against protestors and activists by the authorities and blocked travel within and outside of the country. Compare this with the same time period in 2015-2016, in which there were was only one arrest of an activist. There were only three during these months in 2014-2015 as well. Some are wondering whether this spike in arrests is a coincidence or whether Vietnam is settling into a world where many of its critics’ eyes have turned elsewhere. As such, the US backing out of even symbolic protections of human rights could allow countries like Vietnam to slowly escalate human rights violations, or at the very least, continue them at the same level without penalty.

Trump speaking out against human rights violations would likely do nothing to hurt his administration since he appears to be disinterested in working with the Vietnamese government in the first place. So why not speak up? In fact, condemning Vietnam’s human rights record could provide a way for him to continue to soften his tone and appeal to a broad-based coalition within the US.

While we fervently believe that human rights should be protected for the sake of human dignity, we understand that Trump may need a political incentive of his own to intervene. For example, since Trump needs to curry favor with the US’s religious right, he could acknowledge and condemn the persecution of religious groups in Vietnam. Just last month, a Vietnamese pastor and activist was kidnapped and physically harmed. Additionally, Catholic activist Dang Xuan Dieu was recently released from prison but then immediately forced into exile in France. And then there’s Catholic priest Father Nguyen Van Ly, the man who was released ahead of Obama’s visit last year, who has collectively served decades in prison and is still very active in Vietnam. At the very least, even occasional Trump administration inquiries into Vietnamese government actions could remind them that they are still being monitored.

Dang Xuan Dieu at the Geneva Summit for Human Rights and Democracy, Feb. 21, 2017. Source: Facebook Dang Xuan Dieu

If Trump engages with Vietnam to any significant extent, it could be motivated by worries about China. Trump has positioned himself as a critic of China, framing the competition between the two powers as a battle for international economic superiority. Thus, he may try to buddy up to Vietnam as a counterbalance to China. Another possible scenario, however, and one which is explored by Ralph Jennings of Forbes, is that just as the US self-focuses, Vietnam and China may both turn inward and look towards national and regional issues. Maybe they’ll even have to rely on each other. However, a more unified China and Vietnam could see the two unlikely bedfellows sharing tips on repression of free speech. Both countries are well-known jailers of journalists.

No matter what the US does or does not do under Trump, however, it is crucial to remember that Vietnam is a global actor whose actions are by no means solely determined by the politics of the United States or any other country. Thus, perhaps the starkest scenario is that business-as-usual will continue in Vietnam, unaffected no matter who is in power in the US or elsewhere, nor what global message they send. Where Obama’s administration succeeded by some measures in making Vietnam’s issues known on the global stage, this will not continue under an isolationist Trump administration that censors media and condones repression of dissent itself. And maybe Obama’s strides aren’t lasting anyway, as oppressors in Vietnam have evolved to find new ways to harass activists and cover their tracks. Vietnam has a fully open weapons trade with the US, no Obama to placate, a EU that is preoccupied with other matters, virtually no independent media, and a well-oiled Communist Party machine beneath which it can hide its abuses. Without the ability to even know what is happening inside of Vietnam, how can anyone expect to really change it?

Some hope remains that the EU can push Vietnam on human rights commitments through their own free trade deal. But civil society in-country and elsewhere is continuing to step up as the next line of defense. The problem? Even though US and European civil society groups may be more restricted under nationalist, right-wing leaders, they’re at least allowed to exist. In Vietnam, civil society and the community leaders that hold it up continue to be forced into the shadows.

Given the volatility of the Vietnamese governments’ actions, as well as Trump’s, and the ever-changing nature of the reported news, it is difficult to say which scenario will become our shared reality. Many factors will weigh on the human rights situations in both the US and Vietnam this year, including the gradual roll-out of Trump policies, the elections and power struggles in the EU, and the economic performance of the US, China, and Vietnam. As activists become more charged in their campaigns against Trump in the US and against right wing nationalist groups in the EU, they may find more common ground with their counterparts speaking out against human rights violations in Vietnam. Perhaps the best way to prepare for all possible human rights scenarios is to continue to unite the people and the communities all over the world that are leading the resistance against discrimination and exclusion.

Follow us on Twitter @The88Project as we follow and analyze the unfolding of US-Vietnamese relations in 2017.